…the western fellows took to the name themselves, and concluded it wasn’t such a disgrace to be called a coyote after all, and that the name was rather expressive…

Hello Substack! I am, I think, going to treat this as my first proper post, so that you know what you’re in for ;)

To signpost this, I’m going to talk about the idea that coyotes prey on domestic dogs by luring them away from safety. I’ll go into the history of this notion, and my thought processes around investigating it. Then we’ll get to a shocking twist that, if you are like me, will have you going: oh. Right. And then we’ll talk about how this story has changed over time, and why.

So, shall we begin?

If you’ve never heard this before… well. If you’ve never heard this before, you’ve never read the comments on a YouTube video in which a coyote and a domestic dog appear on screen at the same time. But, to spare you from having to read the comments, the shape of the story is this:

Coyotes, which are generally dog-averse, sometimes act in a playful manner towards them. When they do so, it’s because they are enticing the dogs away from the safety of their owner and towards some place where the rest of the pack lies in wait, so that the dog can be killed and eaten.

To start with, I think there’s a fairly obvious question: does this happen? So as not to keep you in suspense, the answer is no. No, it does not happen. I am not convinced that it has ever happened, although having asked coyote expert Janet Kessler I’m willing to stipulate that there may be a kernel of truth, after all.

I described them as “generally dog-averse,” which is understating the degree of antipathy coyotes have towards dogs. They will play with them, on occasion. They will even mate with them, on yet rarer occasion (more on this later). As a rule, though, they strictly avoid contact.

Coyotes have been known to prey on dogs, especially small dogs; video evidence attests to this. That said, that video evidence belies the extent to which people don’t realize they’re cohabitating with coyotes they rarely see. A 2007 scat analysis of Chicagoland coyotes found domesticated animal remains in 1.3% of samples, with a high of 6.7% in Schaumburg. That, though, was entirely feline; dogs don’t rate a mention1.

Dogs do rate a mention in a similar Canadian study from 20152. There, domestic dog remains were found in <0.5% of urban coyote scat, and <0.1% of rural coyotes (suggesting that it is largely opportunistic predation on unattended dogs, and not—for example—that this is a phenomenon ranchers or farmdog owners are more likely to have observed).

As Stan Gehrt—“America’s go-to biologist for urban coyotes”—put it:

If coyotes were relying on pets as a source of food, we quickly wouldn’t have any pets left.

(From Dan Flores’s excellent Coyote America)

As a reminder, we are specifically interrogating the claim that coyotes lure domestic dogs off to be killed and eaten. “Well, there was a warning about that on Nextdoor” would not be proof that this claim is grounded in reality. “It’s not a myth. My dog was killed by coyotes” also has no bearing on the legend. Nobody is saying no dogs are ever killed by coyotes, after all.

I suggested there might be a kernel of truth to the claim, though. In the course of writing this story, I reached out to Janet Kessler, the foremost expert on coyotes in the San Francisco Bay Area—where they have been present only since the turn of the millennium, and where human-coyote and dog-coyote interactions are common. I wanted to know if anyone had ever looked into where the story came from.

Not that she was aware of. However, she did suggest a possible origin. Coyotes, as wild predators for whom injury is liable to mean death—and not particularly large predators, at that—are likely to retreat if chased by a dog, until they feel safe. When they do, they might feel empowered to try and drive the dog out of their territory.

A dog that was either aggressive to begin with, or that misreads wild-canid body language and responds by continuing to pursue the coyote, could eventually find itself provoking a fight. Up until that point, this behavior could look—especially at a distance—like “play” that suddenly and unpredictably turned hostile.

You will note the number of conditionals in this narrative. Ms. Kessler was not aware of any documented examples of this occurring, and it is not mentioned in Erin Boydston, et al.’s survey of filmed coyote-dog encounters3, although they do note:

Coyotes in agonistic interactions tended to exhibit defensive aggression toward domestic dogs, whether or not dogs escalated encounters to the point of biting. Coyotes may have used defensiveness as an alternative strategy to biting, possibly because they had prior injuries or felt cornered by dogs, humans, and surrounding physical structures.

I am spending so much time on this because I think an important dimension of this story is the perception of coyotes, and the role their interactions with people play in American culture. This, in and of itself, is important when we start to look at where the myth originated.

I have doubted that there was any truth to it for some time, chiefly because there is a marked paucity of first-hand accounts—just a lot of “coyotes are known to” and “coyotes will” and “everyone knows,” which is how you say “this common misconception is widely believed” in Folkloric English.

My initial assumption was that it probably came from the “nature fakers” period, and the current of turn-of-the-century American literature that sought to understand animal behavior through the lens of anthropomorphism. These writers viewed animals as intelligent and deliberative, behaving according to moral precepts just like people.

This did not, of course, mean that all animals benefited equally from this treatment, even as it evolved through the 20th century to give us Baree and Misty of Chincoteague. In nature, a combination of mutual aversion, and the fact that both female and male coyotes are only seasonally receptive, means that coyote-dog hybrids are rare; a 2014 genetic analysis found “no evidence for continued hybridization,” concluding, if it occurred, it was below their detection limit4.

Newspapers, though, thought differently. It’s around the turn of the century that half-coyotes began to appear in the public consciousness. At best, they are uniquely wild, companions of the occasional American Indian tribe that uses them for hunting.

More commonly, they are uniquely vicious—livestock predators of the highest order, wily and spiteful. Their closeness to man has bred contempt for the natural order, and a sort of unique corruption that proved to be enduring. Consider Slasher, the antagonist of Jim Kjelgaard’s Outlaw Red (1953), “product of a big mongrel dog and a female coyote”:

His eyes were clear yellow, and in them seemed to glitter the hate that a hybrid, who could claim no family as his own, felt for the entire world. Slasher was a born killer, a perennial pirate who had so far been too clever to be caught and punished for his misdeeds. In spite of the fact that, on occasion, he led a pack of renegade dogs through the hills, most of the time he preferred to be alone. Slasher had simmered in the juices of his own hatred for so long that not even the few mates he had tried to take could for long put up with him.

To me, it seemed reasonable that the same time period that birthed this trope might have given rise to the myth of Coyote, the Canine Pied Piper. It is the kind of motivated, cunningly intellectual behavior that might plausibly have been ascribed to coyotes. That is the narrative I had in my mind, and which I thought would be nice, tight, and concise.

There’s just one problem: it’s not that old.

A 1940 Blackwood’s Magazine does say: “Coyotes will lure away a farm collie and kill him so they can steal chickens without interruption,” and there are isolated earlier mentions. But, for the most part, the myth doesn’t seem to have taken root until the 1970s. And, for that matter, the late 1970s. The canonical example, from October 1979 as reported the El Paso Times, goes like this:

Foy White, a game warden for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, said there is nothing unusual about coyotes stealing dogs. “Usually one coyote will play where a dog can see it. When the dog comes out to see what is going on, the coyote will lure it farther into the desert where other coyotes will converge and kill it,” White said. He said he was unsure whether they kill dogs for sport or food.

I call this “the canonical example” because it represents an instance of something being declared as “nothing unusual,” by someone who should be an authority figure, who is confidently stating something that we know for a fact to be untrue. This story was circulated through other papers more or less verbatim that year, although the lack of speculation implies to me that it was taken to be at least unsurprising if not common knowledge by that point.

Not that it was universally accepted. A 1983 writer in Kansas reported on a man who “had watched his own dog chase coyotes. Sometimes the coyote would finally stop and turn on the dog. That would end the chase. ‘The dog wanted no part of the coyote,’ the farmer said. He thinks coyotes sometimes bait dogs into chasing them just for the company.” The year before, a waggish anecdote in the Arizona Republic warns:

Many winter visitors, it is said, have made the mistake of unleashing Fifi at an Interstate rest stop to heed nature’s call. Lured by the coyote’s call, many Fifis have defected to form rampaging “poodle packs” that roam the desert and terrorize cattle.

Now, before we turn back the clock, I think it is important to note something else about old reporting. We are looking for instances of this story being recounted, which does not mean that it happened. “Being reported in an old newspaper” says remarkably little about whether something is true. Worse, though, it does not mean that the author was reporting on anything anyone thought was true.

So, when the Atchison, Kansas Atchison Daily Patriot tells us…

The Indians of Palm Springs have a strong belief in the cleverness of coyotes, and have informed me in all seriousness that coyotes are known to steal large watermelons and roll them miles away from where the theft was committed. It is certain that coyotes, when grape hunting, only select the largest and ripest bunches, and they display this sagacity when choosing melons.

…We cannot take it as a given that coyotes actually steal melons. We also cannot take it as a given that “the Indians of Palm Springs” believed this, or that anyone told the reporter this story, or that anything like it was ever told to anyone before appearing in this article. It could just as easily be a bored newspaperman who wanted to knock off early so they could go drinking.

What we would be trying to find, instead, is just evidence that this was an embedded meme. Here is where the twist I mentioned comes in, and some of you are about to say: “oh. Huh, that’s right, isn’t it?” Because this story does come from the turn of the century, and it was well-embedded in the public consciousness, and there is a “nature fakers” connection to it.

It’s just not about coyotes.

As far back as the 1830s, Americans were warning each other that “the wolf sometimes lures a dog into his power, fawning and gamboling around him, by which he is probably mistaken for one of the same species, until an opportunity offers, when he seizes and bears his victim away to his hiding place.”

In 1899, a man relates: “old hunters always advised me to keep my wolf hounds shut up at night, or sooner or later they would be lured out a couple of miles by a single wolf and then set upon by the pack.”

By 1906, the idea was so firmly fixed that it forms the opening of Jack London’s White Fang, in which a hungry wolf lures away the dogs of an isolated sled team, one by one, before starting on the humans.

“It’s a she-wolf,” Henry whispered back, “an’ that accounts for Fatty an’ Frog. She’s the decoy for the pack. She draws out the dog an’ then all the rest pitches in an’ eats ’m up.”

There is an element of sex here, as there was throughout the 19th century—from the 1840s on there have been persistent rumors that wolves will entice domestic dogs not as prey but as mates. That one doesn’t seem to have attached itself to coyotes.

I suspect London has a lot to do with the continued popularity idea of the duplicitous predator, taking advantage of the weak, soft instincts of domestic animals. Well into the mid-20th century, this behavior was ascribed to wolves—“there are many instances,” a 1942 article in the Kirksville Daily Express tells us, “wherein wolves lure dogs away from their masters or other dogs, by running just fast enough and far enough to encourage the dog to chase them into a secluded spot.”

There are other parallels, too, in fiction. Before Jim Kjelgaard went after coydogs, James Oliver Curwood’s Kazan (1914) was… well, the book is called Kazan, the Wolf-Dog. Kazan, unlike Slasher, was a protagonist—but not, clearly, sympathetic for everyone. At the end of the novel, Kazan finds himself taken captive:

“I’ve had your kind before. The dam’ wolves have turned you bad, an’ you’ll need a whole lot of club before you’re right again.”

Did wolves actually do any of this? I mean… probably not. Wolves and dogs seem to be a little more sympatico, so the idea that mushers (and, again, Native Americans—of course. Since they were themselves shorthand for The Wild, they were identified with this habit) regularly cross-bred wolves to improve the stock of their sled dogs is at least a little more plausible. On the other hand, the notion that, as a 1924 article from Ontario claims:

In trading communities where the sled dogs show signs of losing their stamina, the natives very often renew the strain by breeding a dog with a wolf. The female sled dog is chained out where wolves are known to be running in the mating season, and the man who chains her out perches with rifle in the branches of a tree at a convenient distance from her. In due time the leader of the pack appears and immediately after the mating the man in the tree drills a bullet through the wolf. If he failed to shoot, that wolf and the other members of the pack would fall on the dog and tear her to pieces.

…Call me skeptical. Either way, before coyotes regularly enticed dogs to their doom, wolves were the culprit. So what changed? I’m not sure there’s a definitive answer to that, but I’ll propose that three things happened.

One: there were no more wolves. By 1942, Missourians reading the Daily Express were very unlikely to have seen one in the wild. They might not have seen the coyotes that moved in to the resultant vacuum, either—many Chicagoans have not, despite their proliferation in the area—but they were much more likely to be familiar with them, and definitely familiar enough that what a coyote was no longer needed explanation, as it did in the previous century.

Two: probably as a consequence of its dwindling familiarity, the wolf was being rehabilitated in America—as immortalized by Aldo Leopold, famously. But also by, say, Farley Mowat’s 1963 Never Cry Wolf, which is a lot more nature-fakery than it is naturalism. Just as the coyote displaced the wolf in its native biological range, the wolf displaced the coyote as a symbol of the untamed and savage wilderness that Americans saw themselves both as confronting and as identifying with.

It’s just that, after World War 2, said wilderness was no longer a present reality. Wolves, therefore, became totemic: noble predators who mate for life, and raise fuzzy puppies with cute blue eyes as a mutually supportive family. Shaggy, aloof beasts who are nonetheless more afraid of you than you are of them, and whose evocative howl became aspirational when it returned to Yellowstone, and the Pacific Northwest, and just recently to Colorado.

The third thing is, I believe, the flip side of the first two. We could phrase it as: America outgrew the coyote. In the period between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of World War 2, the role coyotes played as emblems of the frontier was a complex but sympathetic one. Coarse but defiant, hardscrabble but resilient, persecuted but ever-adaptable, the coyote was mean, smart, scrappy, spat-on, and ultimately triumphant—just like the pioneers.

Said Colorado naturalist Enos Mills, in 1922:

He is wise, cynical, and a good actor. He has a liking for action and adventure. He really is a happy fellow, something of a philosopher and full of wit […] two nights a coyote raided a settler’s hen-roost and each time left the feathers near my camp. I was ordered out of the country! A common prank of the coyote is to lure a dog from a camp or ranch to a point where the coyote is safe and then to pounce on the dog and chase him back in confusion.

Or, to make the comparison direct, here’s how an 1894 op-ed in Topeka put it, replying to a question about the pejoratively named “coyote districts of Kansas” (the source of the pull quote that opens this piece):

It’s true the coyote as an animal does a good many things which, it would seem, ought to bring to his cheek the blush of shame, but on the other hand he has qualities to be admired. He has rare rustling qualities and remarkable ability to size up the situation. The coyote never starves to death and is an animal of discriminating judgment […] The coyote understands when to run a bluff and he also understands when a bluff would be a most unwise proceeding. The men of the western third of the state have some of the same qualities.

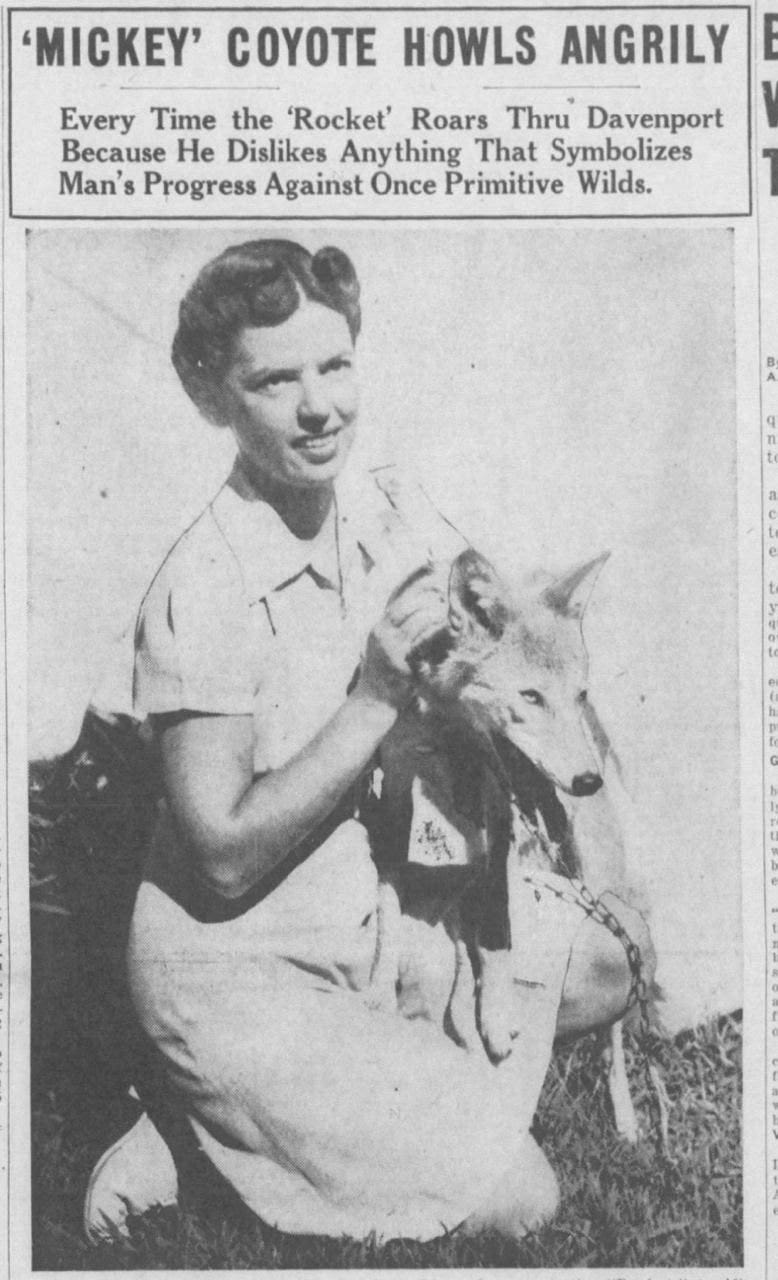

When prospector Adolph Sutro proposed a large drainage tunnel to deal with flooding in the Comstock Lode, they called it “Sutro’s coyote hole.” Newspapers spoke, with some admiration, of Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl as a “coyote Apache,” who was never apprehended. Mickey, here seen in the greatest headline of all time, has a point—we can tell that now as surely as we could back in 1941 when this was published.

Is it any wonder that so many American soldiers, preparing to ship out in the early 40s, adopted coyote mascots? But when they returned, and suburbanization took over, the coyote’s “rustling qualities” were no longer an asset. Nor has there been a Farley Mowat for coyotes, although I suppose Janet Kessler is making a game attempt.

What remains, then, are the aspersions. Ascribed to wolves, as it was originally, the dog-luring myth in 2024 seems nakedly absurd—something you’d easily dismiss, a quaint if telling artifact of a time when the credulous demonized an animal they simply didn’t understand.

(Or, more to the point, viewed as an obstacle to man’s progress against once primitive wilds)

But… doesn’t it sound like something a coyote would do? Can’t you just picture them, skulking through your neighborhood, putting on a friendly face to entice the unwary? Just to be on the safe side, you’d best lock up your watermelons.

You never know who might be watching.

Morey, P., Gese, E., and Gehrt, S. (2007). Spatial and Temporal Variation in the Diet of Coyotes in the Chicago Metropolitan Area. American Midland Naturalist. 158.

Murray, M., Cembrowski, A., Latham, A.D.M., Lukasik, V.M., Pruss, S. and St Clair, C.C. (2015), Greater consumption of protein-poor anthropogenic food by urban relative to rural coyotes increases diet breadth and potential for human–wildlife conflict. Ecography, 38: 1235-1242.

Boydston, E..; Abelson, E..; Kazanjian, A.; and Blumstein, D. (2018) "Canid vs. Canid: Insights into Coyote-Dog Encounters from Social Media," Human–Wildlife Interactions: Vol. 12: Iss. 2, Article 9.

Monzón J., Kays R., Dykhuizen DE. (2014) “Assessment of coyote-wolf-dog admixture using ancestry-informative diagnostic SNPs.” Mol Ecol. 2014 Jan;23(1):182-97.